Anthony S. Chen, Northwestern University

For many Black people in the United States, George Floyd’s killing by a Minneapolis police officer on a Monday evening in late May must have sparked feelings of deep and genuine outrage.

But such feelings could hardly have been new, and they must have been accompanied by a wearying sense of déjà vu. Scores of unarmed Black men and women had been slain by police officers and would-be vigilantes since 2013, when a Florida jury’s refusal to convict Trayvon Martin’s killer of second-degree murder or manslaughter fueled the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. In the eyes of many Black people, Floyd’s killing must have seemed like the latest entry in a lengthy catalog of indignities, atrocities, and tragedies that together formed only the most obvious manifestations of anti-Blackness in American society.

As much as it was a source of outrage for many Black people, Floyd’s killing also surely evoked unsettling memories of their own troubling encounters with the police, and it must have served as a reminder of pained conversations that many of them have had about how to behave around police officers—conversations with their sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers, aunts and uncles, cousins and friends.

George Floyd’s killing held a different significance for many non-Black people in the United States—and especially for many White people.

It could hardly have been a visceral reminder of police brutality to millions of non-Black Americans. The problem had barely registered in their awareness of the world. For many of them, it functioned more like a graphic introduction to police brutality and a primer on how senseless, cruel, and infuriating it could be.

One of their first lessons concerned the drastic way that official accounts could differ from what body-camera footage or bystander videos might later show.

An early statement from the Minneapolis police claimed that Floyd had “physically resisted officers” and was “suffering medical distress.” But a bystander video posted to Facebook conspicuously diverged from the official account, which made no mention of the fact that a White police officer had been casually kneeling on Floyd’s neck for several minutes as he gasped repeatedly, “I can’t breathe.” The officer did not stop even after it was clear that Floyd had been subdued. Shortly before he lost consciousness, Floyd called out for his mother. Not long after, he was dead.[1]

The video’s revelations were a clap of thunder for many non-Black people, and consciences that had slumbered through the deaths of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, John Crawford III, Eric Garner, Laquan McDonald, Sandra Brown, Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and dozens of others, now found themselves jolted awake.

———-

Beyond the unusually shocking nature of the cellphone footage, there are many reasons why George Floyd’s killing might have mattered to a new majority of Americans when all of the killings that went before it did not.

In the New York Times Magazine, Nikole Hannah-Jones notes that years of “unrelenting organizing by the Black Lives Matter movement” were a major reason why. Indeed, from the moment in 2012 when Marcus Anthony Hunter devised the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, to the subsequent year when Alicia Garza posted her “love letter to black folks” on Facebook, to the acts of protest and disobedience that gripped Ferguson, Missouri and then New York City in 2014, to the surprising 2016 declaration of Rahm Emanuel’s Police Accountability Task Force that the Chicago Police Department’s “own data gives validity to the widely held belief the police have no regard for the sanctity of life when it comes to people of color,” Black Lives Matters has led the way.[2]

BLM has been far from the only voice calling for the dignity and humanity of Black people to receive full recognition. There have been other actors who have also demanded a transformation of the justice system. But it is hard to deny that BLM has played a key role in touching off a cascade of interrelated changes in various dimensions of our culture, politics, and society. I would argue that it has made police brutality a policy issue among political elites, and that it has forced elected officials at all levels of government to take a stance. I would further argue that at the level of the mass public it has kept the issue in the forefront of the public imagination at a time when our attention itself has become more of a commodity than ever.

Perhaps most profoundly, however, BLM-led activism around the country may have contributed vitally to the beginnings of a fundamental change in the consciousness and attitudes of many non-Black people. The change was revealed by the May and June protests in such a way that some Black people who I know have reported the feeling of being seen, heard, and understood for the first time in a long time. This feeling, in turn, comes not from a change in Black people but from a growing capacity of many non-Black people to identify with Black people—not just Black athletes and Black rappers but “normal,” non-celebrity Black people. In ever greater numbers, non-Black people and especially White people look at the killing of a Black man like George Floyd and ask themselves questions that had simply not occurred to ask in the past. What would I have felt in the last moments of my life if I were him? How would I feel about what happened to him if he were my brother, son, or father? What must it be like to worry every time someone I love sets foot outside that an encounter between them and the police could go fatally off the rails? In a sense, what BLM’s activism has done is help to precipitate a moment of disenchantment with the racial status quo among growing numbers of non-Black Americans. It gradually seeded skepticism of the odious notion that the violence perpetrated by the police against Black people was simply a case of just deserts. At the same time, it rendered increasingly legible the myriad ways in which police brutality and other expressions of anti-Blackness were actually the consequence of our collective political choices. To borrow the words of Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, BLM’s mobilization over time has led to a piercing of the “prevailing common sense about our society.”[3]

There can be little denying that the outbreak of COVID-19 formed an indispensable context in which the innumerable changes wrought by BLM could potentially take effect. If it makes sense to think of BLM’s mobilization over time as gradually potentiating the possibility of a sea change in public concern about police brutality and anti-Blackness, then the onset of the pandemic was the final ingredient that made the social situation in many parts of the country ripe for a triggering event.

The pandemic has mattered in myriad ways.

Hannah-Jones observes that millions of Americans had been suddenly and unexpectedly thrown into a state of precarity and hardship, and the scales fell from their eyes. Only during a time of pandemic did it dawn on many non-Black people on lockdown at home that delivery drivers, grocery clerks, and many other “essential,” low-wage workers were Black and Latinx. Only during a time of pandemic did many Americans become keenly tuned into the behavior of the police, who they witnessed “beating up white women, pushing down an elderly white man and throwing tear gas and shooting rubber bullets at demonstrators exercising their democratic right to peacefully protest.” If they would unapologetically perpetrate such blatant abuses against White people in the presence of a thousand iPhones, what were they doing to Black people when there were no phones around?[4]

Opal Tometi, who co-founded the Black Lives Matter movement with Alicia Garza and Patrisse Cullors, offers a concurring judgment in an interview recently featured in The New Yorker. Tometi highlights the sociology of emotion behind the shift. For weeks, “we have been sitting in our homes, navigating the pandemic, dealing with loved ones being sick, dealing with a great of fear and concern about what they day and the future will hold.” In more settled times, feelings of empathy and concerns about fairness might have been successfully kept at arm’s length, but such sentiments were now close to the surface and hard to ignore. The collective ordeal brought on by the pandemic has made many of us “more tender or sensitive to what is going on.” Tometi also offers a more practical reason. The pandemic has given people the opportunity to act on their newfound feelings. Many people who would have been at work “now have time to go to a protest or rally.”[5]

It mattered especially that the pandemic happened more than three years into the presidency of Donald J. Trump. Has there been a modern American president whose electoral success has been more centrally and explicitly predicated on the status anxieties of downwardly mobile white Americans than Trump? Has there been a modern American president who has more eagerly stoked the very anxieties that got him elected in the first place? Has there been a period in modern American political history when ideas about race have so sharply differentiated the electoral coalitions of the two major parties?[6]

To a degree that is exceptional in modern times, race is front and center in American politics, and Trump’s openly racist appeals and bald prejudice have led significant numbers of non-Black people to see that anti-Black and anti-Brown racism of the most explicit kind is not some dying atavism of a bygone time or a figment of the liberal imagination. As anticipated by Christopher S. Parker in a 2016 article in The American Prospect and recently highlighted by Dana Milbank, Trump’s “clear bigotry” has rendered it “impossible” for a non-trivial subset of “whites to deny the existence of racism in America,” and it has encouraged them to “honestly confront the persistence of racism as never before.”[7]

By the evening that George Floyd was killed in 2020, Americans had been watching for more than three years as Trump smeared Mexican Americans and praised neo-Nazis as “very fine people,” rarely seeming to pay a political price for his slurs and effrontery. If any non-black Americans were slapping their foreheads in disbelief at his conduct in the initial years of his presidency, they were largely accepting of prejudice and discrimination as an incontrovertible if lamentable fact of life a few years later. As much as BLM or the pandemic, Trump’s promotion of white supremacy was a necessary ingredient for turning George Floyd’s killing into the trigger that it became.

———-

Further research will determine whether these points have any merit, and I certainly hope comparative-historical sociologists will lead the intellectual charge. But what seems difficult to dispute is the remarkable scale, wide scope, and diverse character of the protests that have occurred in the wake of George Floyd’s killing.

This month-long wave of protest began in Minneapolis on May 26. Thousands of people, many of them wearing masks, gathered at 38th Street and Chicago Avenue outside Cup Foods, where Floyd had been killed, and they then marched to the Minneapolis Police Department’s Third Precinct station. The protest in Minneapolis intensified over the next few days and spread to other cities, including New York, Los Angeles, and Atlanta. After several days of unrest, President Trump threatened to suppress the demonstrations, tweeting “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.”[8]

Trump’s echo of a segregationist mantra only seemed to fuel further protest. On the day of his “looting, shooting” tweet—Thursday, May 28—there were perhaps 50 protests around the United States. The number leapt upward sharply each subsequent day. According to data collected by the New York Times, there were 150 protests on Friday, May 29; 400 protests on Saturday, May 30; and then nearly 500 protests on Sunday, May 31. The protests peaked on June 6 (which saw more than 500 protests), but June 13 (which saw 250 protests) and Juneteenth (which also saw around 250 protests) also witnessed major protest activity. By the end of June, there had been more than 4,700 protests in 2,500 cities of varying sizes all across the country. Anywhere from 15 million to 26 million people had participated. The scale and extent of the wave seemed utterly unprecedented. “I’ve never seen self-reports of protest participation that high for a specific issue over such a short period,” Neal Caren is quoted as saying.[9]

As significant as the raw number of protestors involved was their racial composition. Whereas earlier protests led by Black Lives Matter involved participants who were predominantly Black, many American protestors in May and June were not Black. In fact, many were non-Black and indeed White. This is readily discernible in news photos, but it can also be cautiously inferred from the demographics of the locations where protests took place. For instance, one analysis in the New York Times shows that three-quarters of the counties that saw a protest are more than 75 percent white. Better evidence of the racial composition of recent protests is reported by Michael Heaney and Dana Fischer (via Doug McAdams), whose surveys in Los Angeles, New York, and the District of Columbia indicate that something like three-fifths of protestors there were White, while Blacks, Latinx, and Asian protestors each represented about a tenth of protestors.[10]

The protests were not confined to the United States for long. Marches were staged and gatherings were held in London, Bristol, Oxford, Edinburgh, Paris, Osaka, Brussels, Nairobi, Frankfurt, Berlin, Cologne, Toronto, Pretoria, Capetown, Mexico City, and Sydney, to name just a few places. The slogan “Black Lives Matters” appeared not only online in social media but on cardboard placards in the hands of protestors around the world. It is no exaggeration to say that George Floyd’s killing struck a global nerve, leading hundreds of thousands of people outside the United States to take collective action in response.[11]

What seems as equally difficult to dispute as the unprecedented number and diverse makeup of protestors is the rapidity and extent of the shift in public opinion that occurred in the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing.

In a June survey administered by the Monmouth University Polling Institute, three-quarters of those surveyed agreed that “racial and ethnic discrimination in the United States is a “big problem” (compared to two-thirds of those surveyed in 2016). Seven-one percent of White respondents and eighty-four percent of people of color agreed with the statement. In the same June survey, fifty-seven percent of respondents agreed that police officers were “more likely to use excessive force if the culprit is black” (compared to just thirty-four percent in 2016). Half of white respondents and seventy-one percent of people of color agreed with the statement.[12]

The shift is even more apparent when data of higher granularity is examined. Looking at the Civiqs tracking poll of registered voters, Michael Tesler argues that George Floyd’s killing accelerated pre-existing trends. Support for the BLM movement had hovered around forty percent among all respondents for much of 2018, 2019, and 2020. It began ticking upward with the availability of CDC data on COVID-19 by race, and it experienced a sharp jump with Floyd’s death. (Interestingly, so did the percentage of respondents opposing the BLM movement.) Half of all respondents now express support for the BLM movement. A similar jump with Floyd’s death can be seen in the views of white respondents.[13]

Looking at data from UCLA/Nationscape, Tesler observes that sixty-two percent of those surveyed (in the period from May 28 to June 3) agreed that Black people face a significant amount of discrimination, compared to fifty-five percent of those surveyed a week earlier. Fifty-six percent of White respondents agreed, which was seven percentage points higher than the previous week. Over the same stretch of time, it appears that the percentage of White respondents who have a very or somewhat favorable impression of police officers fell from seventy-two percent to sixty-one percent. At the same time, thirty-one percent of White respondents held a somewhat or very unfavorable view of the police, compared to eighteen percent the week earlier.[14]

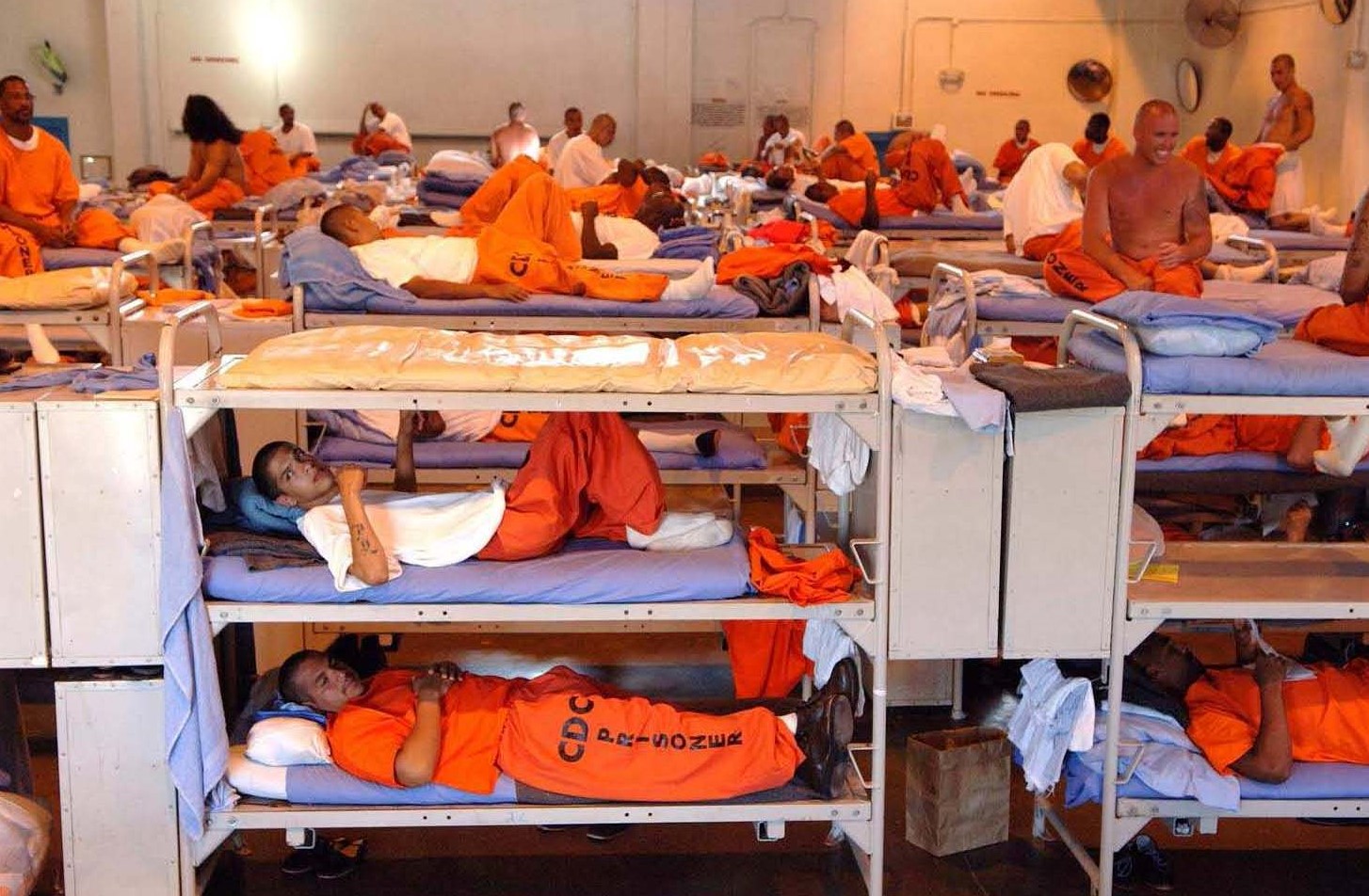

The interracial character of the recent protests and the signs of a shift in public opinion have been accompanied by various degrees of government action. A nominally bipartisan majority in the U.S. House of Representatives approved the “George Floyd Justice in Policing Act” by a 236-181 margin. Although the legislation is a non-starter in the Senate, it nevertheless put a number of long-sought reforms on the congressional agenda. This includes among other things lowering the intent standard in the section of the federal criminal code (18 U.S.C. Section 242) that is currently used to prosecute cases of police misconduct involving the use of excessive force; modifying the section of the federal criminal code (18 U.S.C. Section 1983) that is currently interpreted by the federal courts as giving local and federal law enforcement officers “qualified immunity” from liability in private civil actions in which they have committed constitutional violations; giving the U.S. Attorney General court-enforced subpoena power in “pattern and practice” investigations of law enforcement agencies suspected of violating constitutional rights; providing $750 million to state attorneys general for use in conducting independent investigations of excessive use of force that led to someone’s death, contingent on the passage of state legislation setting up a framework for the independent prosecution of law enforcement; establishing a National Police Misconduct Registry and requiring state and local law enforcement agencies to report all incidents involving use of force to the U.S. Attorney General; banning no-knock warrants in federal drug cases, making the use of chokeholds a civil rights violation, and denying federal monies to localities that do not adopt similar restrictions. Many provisions in the bill will surely serve at minimum as the initial bargaining position for the Democrats in future sessions of Congress.[15]

States and localities have arguably taken more serious steps than the federal government to curb police brutality. Elected officials in Los Angeles and New York City have begun looking at cutting their police budgets. Officers around the country who might not have faced charges for the conduct in earlier times—including George Floyd’s killer—have now been charged by prosecutors with violating the law. California’s state police training program has stopped teaching choke holds; Memphis police officers must now restrain colleagues who are engaging in misconduct or face consequences; Kansas City’s mayor has committed to having every local police shooting reviewed by an external party; Seattle has banned the practice of covering up badge numbers. These are admittedly small changes, and they may not eventually add up to comprehensive reform, but many of them are more substantive than the responses of Congress or the Trump administration.[16]

The stirrings of broader social change are evident as well. Mississippi retired its state flag, which prominently featured a symbol of the Confederacy. A statue of Stonewall Jackson was removed from Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia. A statue of Jefferson Davis was taken away from the rotunda of the state capitol building in Frankfort, Kentucky. In the private sector, thousands of American companies have asserted that Black lives matter and vowed to make good on their proclamations. Some of them have even committed real resources. Doug McAdams points out that Comcast announced it was allocating $100 million over three years to “fight injustice and inequality against any race, ethnicity, sexuality orientation, or ability.” McAdam also guardedly highlights the symbolic significance of NASCAR’s ban on the Conference flag and the NFL commissioner Roger Goodell’s mea culpa, in which he confessed the error of the league’s earlier ways and proclaimed that “we, the National Football League, believe black lives matter.” Many such examples exist, McAdams writes. “Put together, we appear to be experiencing a social change tipping point that is as rare as it is potentially consequential.”[17]

———-

“It feels different this time,” writes Hannah-Jones. BLM’s Tometi agrees. Many other close observers share the same sentiment. “I can’t believe I’m going to say this,” said Ta-Nehisi Coates in a recent interview with Ezra Klein. “But I see hope. I see progress right now.” What is different about the current moment is the fact that “significant swaths” of non-Black people in places like Des Moines and Salt Lake City and Berlin and London care about the “pain” and “suffering” of “black folks in their struggle against the way the law is enforced in their neighborhoods.” Much of the credit for the transformation of the collective consciousness, he believes, should go to BLM. “Within my lifetime, I don’t think there’s been a more effective movement than Black Live Matter.”[18]

It therefore seems fitting that Alicia Garza, another one of BLM’s three founders, feels a sense of hope as well. Just a few years ago, she observed, Garza and her fellow activists struggled to simply assert that Black lives matter without getting an earful of unmitigated grief. “Now everybody’s saying Black lives matter. The question now is, ‘Well, what do you mean? I would say that’s progress.’” It is a huge achievement that BLM is a “major part of our global conversation right now,” when things are just “bonkers.” And what it is doing is “forcing people across all walks of life, all sectors in our economy, and every corner of the planet really, to assess whether we are where we need to be—and what we need to do to get to where we’re trying to go.”[19]

Despite all of the optimism, few close observers are under the illusion that transformative potential of the current moment can be identified easily or realized immediately. There is a keen awareness that additional phases of conscious, sustained struggle are required and that it will be necessary to address and overcome the limits of the initial phase. Garza stresses the importance of making sure “we keep this momentum going where everybody feels like this is a movement that is theirs. It’s not just for Black people.”[20]

There is also a sense that BLM might need to address organizational limits that have held it back from being even more effective. Taking stock of BLM last fall, Yamahtta-Taylor expressed a concern that the decentralized, leaderless structure set up by the organizers was not suited to creating the organic goodwill that they wanted to exist at the heart of the movement. Instead, it simply ignored the growing tension within BLM between a reformist contingent (interested in body cameras and the like) and a “revolutionary” contingent (interested in the abolition of the carceral state). Nor did such a decentralized structure make it possible for the movement to build cumulatively on the lessons that were there to be learned. “The lack of clear entry points into movement organizing, and the absence of any democratically accountable organization or structure within the movement” made it challenging to “evaluate the state of the movement, delaying its ability to pivot and postponing the generalization of strategic lessons and tactics from one locality to the next or from one action to the next.” Each locality often wound up reinventing the wheel. Yamahtta-Taylor was also concerned that BLM’s ethos of leaderlessness was not serving it particularly well. “The issue is not whether there are leaders, it is whether those leaders are accountable to those they represent.” The ideology of “horizontalism” that guided it often caused confusion or led to “hard feelings,” and it made it difficult to course-correct when things began going in the “wrong direction.”[21]

The biggest question of all naturally is whether the current moment will lead to more than stopgap measures, symbolic gestures, and incremental improvements. Is the optimism justified? What kind of enduring achievements and institutional changes will come of it, if any? “It doesn’t take a lot, nor does it cost a lot, to protest the torture and killing of a man on video,” says Vince Hutchings. Grappling seriously with the “original sin of racism is going to take a lot more than condemning murderous police officers.”[22]

Especially sobering is the idea that the remarkable wave of protests that we witnessed in May and June—and the green shoots of social change that have emerged in their wake—have been possible only because one of the most compelling social movements in the last fifty years found itself mobilizing in the context of a once-in-a-century pandemic after three years of shambolic rule by the most bigoted man to sit in the Oval Office since perhaps the Civil War. [23]

The protests are exceptional, for sure. But they have come out of exceptional times. What happens if our times become less exceptional? Will the current sense of urgency dissipate? Will the concern of non-Black people about the dignity and equality of Black people fade away as the pandemic is gradually overcome and economy begins to right itself? Will public concern be satisfied by incremental reforms that do little to challenge the power of police unions once the outrage over George Floyd subsides? Will the outrage be hijacked by other actors with other aims?

———-

There have been times in the American past when the momentum for social change borne of an exceptional moment was sustained and led to meaningful institutional achievements. One example that comes to my mind is the two-and-a-half-year stretch from the Birmingham campaign in 1963 to the enactment of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

This remarkable period began with one of the most exceptional episodes of collective action in U.S. history, one that remains central to the study of social movements to this day. The campaign to dismantle segregation in Birmingham, led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and Fred L. Shuttlesworth of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, involved a boycott of local businesses followed by an escalating succession of mass demonstrations. Thousands of Black people participated in various ways throughout April and May, including the Black schoolchildren who famously took to the streets in the face of police dogs and water cannons.[24]

The situation came to a head on May 7, according to Aldon D. Morris’s authoritative analysis. That day, thousands of protestors were able to flood the unguarded downtown business district after a team of decoy marchers around the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church succeeded in distracting the police. This made it impossible for local authorities to control the situation. Nothing could be done about the downtown protestors, as Birmingham’s jails were already full from days of arrests. The economic and political order had clearly broken down, and the city’s business leaders capitulated early the next morning, conceding most of the movement’s demands. Not long afterward, the Kennedy administration accepted the need for a legislative approach. Birmingham contributed mightily to the nationalization of the civil rights issue. It was a stunning achievement for a disenfranchised people, made possible by the exceptional circumstances that they themselves had been responsible for creating.[25]

There was no backsliding in the two or three years after Birmingham, as exceptional as it was. In fact, Birmingham might well be seen an initial, catalytic step in a dynamic sequence that culminated with the Voting Rights Act.

What followed the Birmingham campaign was a clear intensification of mass mobilization and political engagement, much of it led by an overlapping (and sometimes competing) set of actors. Birmingham provided a “model of protest” for protestors elsewhere in Morris’s words. In the weeks thereafter, several hundred demonstrations took place in scores of cities throughout the South, and civil rights groups organized the now-storied March on Washington at the end of the summer. By the end of 1963, it was clear that Black protest events had leapt sharply upward over the previous two years. News coverage of the four most prominent civil rights groups also shot up, and the volume of pro-civil rights letters written to the White House similarly increased. [26]

In 1964, there was a falloff in the raw frequency of protest events, news coverage, and constituency mail, but there was still a great deal of notable activity. This was the year of Freedom Summer; the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner; the passage of the Civil Rights Act; and the controversy over the seating of delegates from the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City.[27]

The subsequent year saw high levels of mass mobilization and political engagement reach a peak. Black protest activity swing sharply upward again. There were nearly 250 Black protest events in 1965, nearly twice as many as 1963. Many of them were connected to the campaign to win federal legislation on voting rights, based in Alabama and led by the SCLC’s King and the late John Lewis, then chairman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. News coverage also remained at a high level, and Johnson’s White House saw a deluge of constituency mail, more than tripling the volume that had been generated in 1963. A large number of letters came in the wake of Bloody Sunday, the murders of Rev. James Reeb and Viola Liuzzo, and Johnson’s address to a joint session of Congress. The culminating achievement of the period was the passage of the Voting Rights Act, which no less a constitutional authority than Lawrence H. Tribe has pronounced “probably the most radical piece of civil rights legislation since Reconstruction.”[28]

———-

The comparison between our current moment and the years from Birmingham to the Voting Rights Act is not just inexact. The outcome of the May and June protests is simply not known. What kind of case is it? We do not know right now; we cannot know yet. It is possible that little will come of the current moment. The possibility for major change may simply fade after the arrival of a vaccine and a Biden election. There could be backsliding or backlash. Perhaps the moment that should come to mind is not the mid-1960s but the late-1960s. A study by Omar Wasow exploits rainfall as an instrumental variable to show that “protestor-initiated violence” in 1968 “tipped” the election toward Nixon. A comparison should be approached with the utmost caution.[29]

To the extent that it is valid to think about the current moment as a case of success analogous to the mid-1960s, what a comparison suggests to me is the relevance of federal action to significant, lasting change. In a widely read essay in Medium, President Obama argues that protest is important because it raises public awareness and discomfits the “powers that be.” But he also argues that political participation and electoral politics are important because our “aspirations” are translated into “specific laws and institutional practices” in our democracy only when “we elect government officials who are responsive to our demands.” President Obama goes on to point out that that “the elected officials who matter the most in reforming police departments and the criminal justice system work at the state and local levels.” Mayors appoint police chiefs and bargain collectively with police unions. District attorneys and state’s attorneys decide whether to investigate, charge, and prosecute the perpetrators of police misconduct. Hence our current moment could be a turning point for “real change” because protest and politics have come together in a way that responsive governance is actually possible.[30]

Yet it is not clear that the state and local officials are capable of responding effectively to newly resonant demands for “real change” without robust federal assistance. Police unions continue to wield enormous political power in most cities. In a sharply observed portrait of the New York City Police Benevolent Association (NYPBA), William Finnegan argues convincingly that it has thoroughly succeeded in not just winning generous salaries and retirement benefits for its members, but it has also dominated various aspects of public policy. For instance, there has been no requirement that police officers live in the five boroughs since the sixties. Finnegan points out that the NYCPBA has succeeded for decades in rebuffing every attempt to restore it, and a majority of white members continue to live in Long Island and other nearby suburbs. When it comes to public policy around brutality and misconduct, police union influence translates into collective bargaining agreements that shield the “bad apples” (maybe ten percent according to analysts most favorable to police). Typical contracts are stuffed with provisions that often make it difficult to collect the most elementary evidence that is needed to establish whether brutality or misconduct occurred in the first place, and many contracts require binding arbitration if major discipline is meted out to officers. Even if voters wanting real change manage to elect state and local officials who intend to be responsive to their constituents, other political actors like police unions remain powerful enough to thwart reform—major or minor. Various types of federal action might be necessary to make local and state government sufficiently responsive.[31]

Here the comparison to voting rights reminds us that it has previously been the case that federal action was ultimately necessary in order to encourage change on the part of state and local officials. Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which required covered jurisdictions to obtain “federal pre-clearance” before making any changes to their election procedures, was necessary because state and local officials had been enormously creative over the years in their disenfranchisement of Black people, and pre-clearance was necessary to make sure that changes state and local officials wished to make that seemed innocent on their face did not simply make things worse for Black people.

Similarly, federal action seems necessary today, albeit for different reasons. If the George Floyd protests have finally convinced state and local officials to respond robustly to voter demands, they still need all the help they can get when trying to restructure police union contracts in a way that makes police officers accountable for their misconduct.

Is the difficulty of achieving democratic representation at the state and local level a reason to abandon reform in favor of a full-throated abolitionist agenda? Perhaps it is, but I am not so sure yet.

Even if the Minneapolis Police Department’s embrace of “procedural justice” reforms did little to prevent George Floyd’s killing, it strikes me that other types of reform may still be worth exploring. David Thacher argues persuasively to my mind that the police are unique as a government institution because they are invested with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, and a “meaningful agenda” for reform should aim to help the police resolve problems that might require the use of force with as little force as possible.[32]

This will necessitate among other things the adoption of a new portfolio of policies designed to regulate use of force; to monitor compliance with these regulations; and to give the police the capacity to address the wide range of situations they encounter in a manner that uses the minimal degree of force necessary.[33]

One of the most compelling ideas along these lines was introduced several years ago in the aftermath of Laquan McDonald’s killing in Chicago. Max Schazenbach argued that mayors and police superintendents should be given the authority “to fire any officer for any reason that does not otherwise violate a general employment statute.” This authority would be used to purge the police department of problematic, abusive officers. A “less dramatic” change would be to “prohibit local governments from paying for officers’ settlements in civil rights cases” and “require officers to buy professional liability insurance.” Officers exceeding regulations on the use of force or accumulating too many complaints would simply be priced out of the market for insurance.[34]

One sign of the latter idea’s promise is the movement recently afoot among some insurers and brokers to design the kind of professional liability coverage that Schanzenbach had in mind. In response to New York state senator Alessandra Biaggi’s proposal to require officers to carry insurance covering liability for excessive force and abuse, companies like Marsh & McLennan, Hylant Group, and Prymus Insurance are looking into how to set premiums and structure payouts. There is not yet a consensus about the viability of such a product, but some companies believe that “this is absolutely something they will be able to work with.”[35]

Still, putting either of Schanzenbach’s ideas into place—or pursuing other kinds of meaningful reform—would very likely require modifying union contracts, which would in turn require mayors to muster up enough political will to win the right set of contractual provisions in the next round of collective bargaining.

This is where it is not hard to imagine that the federal government could play a powerful and beneficial role. One conceivable way to incentivize mayors and cities to be more responsive to demands for stronger policies would be for the federal government to step in and offer reinsurance for professional liability coverage on certain terms.

Reinsurance is basically insurance for insurers, and it is purchased by insurers (or self-insured entities) who wish to offload specified financial risks that they face as a result of the insurance policies they have written. In the context of health care insurance, for example, some states have created reinsurance programs for health insurers in the individual market. Insurers who participate in the state program are provided payment for some portion of the cost for their enrollees above a certain amount. Successful reinsurance programs can help to lower premiums and maintain the viability of a market that might not otherwise be able to function properly.

A federal reinsurance program for professional liability coverage might work by picking up a substantial portion of the payment for all losses above a certain threshold incurred by an insurer or self-insured municipality due to “wrongful acts” by a covered officer. (This is technically called “specific stop-loss excess insurance.” A policy that covers aggregate losses by an insurer for a particular period of time is called “aggregate stop-loss excess insurance.”) Depending on exactly where the threshold is set, which is a decision that would naturally affect the pricing of the premium, such a program could save large cities a substantial sum of money. These cities are usually self-insured and pay out millions of dollars each year in misconduct cases. For smaller cities that purchase professional liability coverage, such a program could potentially lower premiums and encourage more insurers to participate in the market.[36]

The way that a federal reinsurance program might be leveraged to catalyze responsiveness on the part of state and local officials is that federal reinsurance coverage could be made contingent upon the maintenance of high underwriting standards on the part of insurers. The federal reinsurance program would work directly with self-insured cities (instead of working with insurers), and here coverage could also be made contingent upon high underwriting standards. These high standards would be geared toward loss prevention, and they could include (for instance) whether the mayor and the police chief have the authority to fire officers without being subject to reinstatement by an arbitrator; whether there is a “cooling off” period before an officer accused of misconduct is obliged to make a statement about what happened; whether the police department penalizes officers for making false statements about misconduct; whether there are detailed guidelines on the use of force; whether compliance with those guidelines is monitored; and whether officers are trained to resolve situations using the least amount of force necessary.

Hence the establishment of a federal reinsurance program could potentially give state and local officials a financial incentive to heed demands from their constituents for meaningful reform; furthermore, it could help to set a nationwide “floor” for the reform of use of force policies.

Just as federal action once proved necessary to extending the franchise to Black people in the United States, federal action may well be essential to defeating the scourge of police brutality in the current moment. Depending on the next phase of mobilization, if there is one, police brutality could just be the beginning. It is not inconceivable that some form of reparations could move squarely into the national discussion. Regardless, without a considered degree of federal involvement, meaningful reform of any kind seems out of reach, no matter how powerful the calls for change become.

———-

The subfield of comparative-historical sociology operates at a remove from the most immediate issues that gave rise to the George Floyd protests, but it is certainly implicated in the larger system of anti-Blackness of which police brutality is only one expression.

In comparative-historical sociology, anti-Blackness is manifested in myriad ways. It is recognizable in our canon, our syllabi, our topics of investigation, our lists of award-winning authors, our elected leadership, our editorial boards, and our new hires. In these and other areas of our intellectual and professional life, there are simply fewer Black sociologists in the mix than there should be.

These issues were foremost in the minds of the Officers and Council of the ASA CHS Section in the second week of June, as all of us discussed what to do in response to the protests sweeping the country. (The protests had just reached their second and highest peak on June 6, although we obviously could not have known it at the time.) Several us had learned that the Inequality, Poverty, and Mobility Section under the leadership of David Brady had decided to donate all of the funds that would have gone to finance their conference reception to the ASA Minority Fellowship Program, and there was a strong sense that ASA CHS should consider doing likewise. But there was also a sense that it was incumbent upon us to do more. In particular, we felt that it was important to publicly express our solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement and Black people more generally. At the same time, we felt that our expression of solidarity would be even more meaningful if we took serious steps to identify and address anti-Blackness and anti-Black racism in our own intellectual backyard—that is, comparative-historical sociology.

Over the course of the week, we sought to take steps that would begin to address these issues. We decided to contribute a large portion of our reception funding to the ASA Minority Fellowship Program, and we drafted and unanimously approved a statement of solidarity that articulated our basic values and commitments. (See inset.)

We also resolved to take a moment at the next Council meeting to form a Standing Committee on Anti-Blackness and Racism in Comparative-Historical Sociology. The basic charge of the committee would be to identify and address manifestations of anti-Blackness in our subfield. It might do so in a number of ways. It might undertake an analysis of graduate syllabi at top departments to determine the extent to which Black authors are underrepresented. It might consult with the Elections Committee to help develop a sufficiently diverse pool of candidates for annual elections. It might be asked annually by Section Chairs to assess whether the Section’s program each year reproduces a larger pattern of anti-Blackness.[37]

Lastly, we resolved to commission a panel on “Identifying, Confronting, and Addressing Anti-Blackness and Racism in Comparative-Historical Sociology” at the next CHS mini-conference.

These are modest actions and initiatives when compared to bigger steps that are needed to take down police brutality and challenge the carceral state. But they are actions and initiatives that are borne out of the same moment of collective recognition that gripped many non-Black people around the world in the wake of George Floyd’s killing—that anti-Blackness must be confronted now in all of its multifarious incarnations and that comparative-historical sociologists must not shrink from doing our part.

[1] On the circumstances of Floyd’s killing, see Audra D.S. Burch and John Eligon, “Bystander Videos of George Floyd and Others Are Policing the Police,” New York Times, May 26, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/26/us/george-floyd-minneapolis-police.html (accessed July 15, 2020). See also “Video shows man dying under officer’s knee,” Minneapolis StarTribune, May 26, 2020, https://video.startribune.com/video-shows-man-dying-under-officer-s-knee/570780382/ (accessed July 15, 2020).

[2] Nikole Hannah-Jones, “What is Owed,” New York Times Magazine, June 30, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/24/magazine/reparations-slavery.html (accessed July 9, 2020); Marcus Anthony Hunter, “How does L.A.’s racial past resonate now?” Los Angeles Times, June 8, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2020-06-08/six-writers-on-l-a-and-black-lives-matter (accessed July 9, 2020); Jamilab King, “#blacklivesmatter: How three friends turned a spontaneous Facebook post into a global phenomenon,” California Sunday Magazine, March 2015, https://stories.californiasunday.com/2015-03-01/black-lives-matter/ (accessed July 9, 2020); Chicago Police Accountability Task Force, Recommendations for Reform – Executive Summary (April 2016), p. 8, https://chicagopatf.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/PATF_Final_Report_Executive_Summary_4_13_16-1.pdf (accessed July 9, 2020), cited in Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, “Five Years Later, Do Black Lives Matter?” Jacobin, September 30, 2019, https://jacobinmag.com/2019/09/black-lives-matter-laquan-mcdonald-mike-brown-eric-garner (accessed on July 9, 2020).

[3] Taylor, “Five Years Later.”

[4] Nikole Hannah-Jones, “What is Owed.”

[5] Isaac Chotiner, “A Black Lives Matter Co-Founder Explains Why This Time Is Different,” The New Yorker, June 3, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/a-black-lives-matter-co-founder-explains-why-this-time-is-different (accessed July 14, 2020).

[6] On the status-based nature of Trump’s appeal, see Christopher S. Parker and Matt Barreto, “The Great White Hope: Polarization and Threat in the Age of Trump,” in Democratic Resilience: Can the United States Withstand Rising Polarization, edited by Robert C. Liberman, Suzanne Mettler, and Kenneth M. Roberts (forthcoming manuscript, on file with author); Christopher S. Parker, Change They Can’t Believe In: The Tea Party and Reactionary Politics in America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013); Diana Mutz, “Status threat, not economic hardship, explains the 2016 presidential vote,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, V115, N9 (2018): E4330-E4339. For research that stresses economic factors, such as exposure to trade with China, see David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon Hanson and Kaeh Majlesi, “A Note on the Effect of Rising Trade Exposure on the 2016 Presidential Election,” working paper, https://economics.mit.edu/files/12418, accessed July 14, 2020 and David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon Hanson, and Kaveh Majlesi, “Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure,” American Economic Review, forthcoming. For evidence on the success of Trump’s ethnic and racial appeals in attracting white, working-class voters, see Alan Abramowitz and Jennifer McCoy, “United States: Racial Resentment, Negative Partisanship, and Polarization in Trump’s America,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681 (January 2019): 137-156. On the role of race in fueling a growing feeling of mutual antipathy that obtains between the electoral coalitions of the two major parties, see Nicholas A. Valentino and Kirill Zhirkov, “Blue is Black and Red is White? Affective Polarization and the Racialized Schemas of U.S. Party Coalitions,” working paper, n.d., https://economics.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj9386/f/pe_04_17_valentino.pdf, accessed July 14, 2020.

[7] Christopher S. Parker, “Do Trump’s Racist Appeals Have a Silver Lining?” The American Prospect, May 19, 2016, https://prospect.org/power/trump-s-racist-appeals-silver-lining/ (accessed July 14, 2020); Dana Milbank, “A massive repudiation of Trump’s racist politics is building,” Washington Post, July 3, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/07/03/massive-repudiation-trumps-racist-politics-is-building/ (accessed July 14, 2020).

[8] Ryan Faircloth, “Rubber bullets, chemical irritant, water bottles in the air as thousands march to protest George Floyd’s death,” Star Tribune, May 27, 2020, https://www.startribune.com/rubber-bullets-chemical-irritant-water-bottles-in-air-as-thousands-march-to-protest-george-floyd-s-death/570786992/

(accessed July 15, 2020); “Protestors march after death of George Floyd while in custody of Minneapolis police,” Star Tribune, May 26, 2020, https://video.startribune.com/protesters-march-after-death-of-george-floyd-while-in-custody-of-minneapolis-police/570785262/ (accessed July 15, 2020); Andy Mannix, “Minneapolis police station set on fire,” Star Tribune, May 29, 2020, https://www.startribune.com/minneapolis-police-station-set-on-fire-protesters-march-downtown/570849592/ (accessed July 15, 2020); “George Floyd Protests: A Timeline,” New York Times, July 10, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/article/george-floyd-protests-timeline.html (accessed July 15, 2020).

[9] Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui, and Jugal K. Patel, “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History,” New York Times, July 3, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html (accessed July 15, 2020).

[10] Audra D.S. Burch, Weiyi Cai, Gabriel Gianordoli, Morrigan McCarthy, and Jugal K. Patel, “How Black Lives Matter Reached Every Corner of America,” New York Times, June 13, 2020.https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/13/us/george-floyd-protests-cities-photos.html (accessed July 15, 2020); Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui, and Jugal K. Patel, “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History”; Doug McAdams, “We’ve Never Seen Protests Like These Before,” Jacobin, June 20, 2020, https://jacobinmag.com/2020/06/george-floyd-protests-black-lives-matter-riots-demonstrations (accessed July 15, 2020).

[11] Washington Post Staff, “How George Floyd’s death sparked protests around the world,” Washington Post, June 10, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/world/2020/06/10/how-george-floyds-death-sparked-protests-around-world/ (July 16, 2020).

[12] Monmouth University Polling Institute, “Protestors’ Anger Justified Even If Actions May Not Be,” June 2, 2020, p. 4-5, https://www.monmouth.edu/polling-institute/documents/monmouthpoll_us_060220.pdf/

(accessed July 16, 2020).

[13] Michael Tesler, “The Floyd protests have changed public opinion about race and policing,” Washington Post, June 9, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/06/09/floyd-protests-have-changed-public-opinion-about-race-policing-heres-data/ (accessed July 16, 2020); Civiqs, “Do you support or oppose the Black Lives matter movement?,” https://civiqs.com/results/black_lives_matter?uncertainty=true&annotations=true&zoomIn=true (accessed July 16, 2020).

[14] Tesler, “The Floyd protests have changed public opinion about race and policing”; Rebecca Morin, “Percentage grows among Americans who say Black people experience a “great deal” of discrimination, survey shows,” USA Today, June 8, 2020, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/06/08/survey-higher-percentage-us-agree-black-people-face-discrimination/3143651001/ (accessed July 16, 2020).

[15] Congressional Record—House, June 25, 2020, H2440-2453, https://www.congress.gov/116/crec/2020/06/25/CREC-2020-06-25-pt1-PgH2439-4.pdf (accessed July 16, 2010); Catie Edmondson, “House Passes Sweeping Police Bill Targeting Racial Bias and Use of Force,” New York Times, June 25, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/25/us/politics/house-police-overhaul-bill.html (accessed July 16, 2020).

[16] Paresh Dave, “Factbox: What changes are governments making in response to George Floyd protests?” Reuters, June 10, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-minneapolis-police-protests-response/factbox-what-changes-are-governments-making-in-response-to-george-floyd-protests-idUSKBN23I01D (accessed July 16, 2020).

[17] Rick Rojas, “Mississippi Lawmakers Vote to Retire State Flag Rooted in the Confederacy,” New York Times, June 28, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/28/us/mississippi-flag-confederacy.html (accessed July 16, 220); Alan Taylor, “The Statues Brought Down Since the George Floyd Protests Began,” The Atlantic, July 2, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2020/07/photos-statues-removed-george-floyd-protests-began/613774/ (accessed July 16, 2020); Doug McAdams, “We’ve Never Seen Protests Like These Before”; Brian Robert, “Comcast Announces $100 Million Multiyear Plan to Advance Social Justice and Equality,” June 8, 2020, https://corporate.comcast.com/press/releases/comcast-announces-100-million-multiyear-plan-social-justice-and-equality (accessed July 16, 2020).

[18] Nikole Hannah-Jones, “What is Owed”; Isaac Chotiner, “A Black Lives Matter Co-Founder Explains Why This Time Is Different”; Ezra Klein, “Why Ta-Nehisi Coates is hopeful,” Vox, June 5, 2020, https://www.vox.com/2020/6/5/21279530/ta-nehisi-coates-ezra-klein-show-george-floyd-police-brutality-trump-biden (accessed on July 16, 2020).

[19] Rachel Hartigan, “She co-founded Black Lives Matter. Here’s why she’s so hopeful for the future,” National Geographic, July 8, 2020, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/07/alicia-garza-co-founded-black-lives-matter-why-future-hopeful/ (accessed July 16, 2020).

[20] Hartigan, “She co-founded Black Lives Matter. Here’s why she’s so hopeful for the future.”

[21] Taylor, “Five Years Later, Do Black Lives Matter?”

[22] Dan Balz, “The politics of race are shifting, and politicians are struggling to keep pace,” Washington Post, July 5, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/politics/race-reckoning/ (accessed July 16, 2020).

[23] Jon Meacham argues that Trump is the most racist president since Andrew Johnson. See Shane Croucher, “Trump Is Most Racist President Since Andrew Johnson, Says Historian,” Newsweek, July 16, 2019, https://www.newsweek.com/trump-racist-president-andrew-johnson-historian-tweet-1449449 (accessed July 20, 2020).

[24] Harvard Sitkoff, The Struggle for Black Equality (New York: Hill and Wang, 2008), Chapter 5.

[25] Aldon D. Morris, “Birmingham Confrontation Reconsidered: An Analysis of the Dynamics and Tactics of Confrontation,” American Sociological Review 58 (October 1993): 623.

[26] Morris, “Birmingham Confrontation Reconsidered”; J. Craig Jenkins and David Jacobs, “Political Opportunities and African American Protest,” American Journal of Sociology V109, N2 (September 2003): 287; Edwin Amenta, Neal Caren, Sheera Joy Olasky, and James E. Stobaugh, “All the Movements Fit to Print: Who, What, When, Where, and Why SMO Families Appeared in the New York Times in the Twentieth Century,” American Sociological Review 74 (August 2009): 647; Taeku Lee, Mobilizing Public Opinion: Black Insurgency and Racial Attitudes in the Civil Rights Era (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 127, 131, 133.

[27] Sitkoff, The Struggle for Black Equality.

[28] Jenkins and Jacobs, “Political Opportunities and African American Protest,” 287; Amenta et al, “All the Movements Fit to Print,” 647; Lee, Mobilizing Public Opinion, 127, 131, 133; Lawrence H. Tribe, American Constitutional Law (New York: Foundation Press, 1978), 336. The radicalism of the Voting Rights Act inhered in the fact that the legislation did not simply provide for enforcement of a generic new prohibition again treating individuals in a discriminatory way. Instead, it banned or called into question specific voting practices, such as the literacy test and poll taxes. One of the most robust provisions, Section 5 required covered jurisdictions that wanted to change their election laws to first obtain permission from the federal government, and the formula that determined coverage was based on whether a jurisdiction’s level of voter participation met specific numerical thresholds at particular moments in time. Hence the Voting Rights Act did not take an individualistic approach to protecting the franchise; it took a more structural and substantive approach that was motivated not by abstract ideals like “freedom from discrimination” but historically specific instances of injustice.

[29] Omar Wasow, “Agenda Seeding: How 1960s Black Protests Moved Elites, Public Opinion and Voting,” American Political Science Review V114, N 3 (August 2020): 638-659. Wasow argues that the Floyd protests started out like protests in 1968 and became more like protests in 1964. Omar Wasow, “The protests started out looking like 1968. They Turned into 1964,” Washington Post, June 11, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/06/11/protests-started-out-looking-like-1968-they-turned-into-1964/ (accessed August 3, 2020).

[30] Barack H. Obama, “How to Make This Moment the Turning Point for Real Change,” Medium, June 1, 2020, https://medium.com/@BarackObama/how-to-make-this-moment-the-turning-point-for-real-change-9fa209806067 (accessed July 24, 2020).

[31] William Finnegan, “How Police Unions Fight Reform,” New Yorker, July 27, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/08/03/how-police-unions-fight-reform (accessed July 29, 2020); Max Schanzenbach, “Union contracts key to reducing police misconduct,” Chicago Tribune, November 23, 2015, https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-police-excessive-force-laquan-mcdonald-perspec-1124-20151123-story.html (accessed July 24, 2020). On the problematic role of prosecutors in holding police accountable for misconduct, Kristy Parker, “Prosecute the Police,” The Atlantic, June 13, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/prosecutors-need-to-do-their-part/612997/ (accessed July 24, 2020). For an open-source database of police contracts, see www.checkthepolice.org.

[32] David Thacher, “The Crisis of Police Reform,” unpublished manuscript on file with the author. See also David Thacher, “The Limit of Procedural Justice,” Police Innovation: Contrasting Perspectives, edited by David Weisburd and Anthony A. Braga (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006) and David Thacher, “The Learning Model of Use-of-Force Reviews,” Law and Social Inquiry V45, N3 (August 2020): 755-786.

[33] Thacher, “The Crisis of Police Reform.”

[34] Schanzenbach, “Union contracts key to reducing police misconduct.”

[35] Suzanne Barlyn and Alwyn Scott, “U.S. Carriers Begin Crafting Police Professional Liability Cover,” Carrier Management, July 24, 2020, https://www.carriermanagement.com/news/2020/07/24/209484.htm (accessed July 29, 2020); Biaggi’s proposal would require local governments to pay a basic premium for every officer, but any premium increases stemming from the misconduct of a particular officer would be borne by the officer themself. On the kind of liability insurance currently purchased by small cities around the country and the role of insurers in reforming the police, see Kit Ramgopal and Benda Breslauer, “The hidden hand that uses money to reform troubled police departments,” NBC News, July 19, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/hidden-hand-uses-money-reform-troubled-police-departments-n1233495 (accessed, July 29, 2020). But see especially John Rappaport, “How Private Insurers Regulate Public Policy,” 130 Harvard Law Review 1539 (2017), https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ccfe/86d2cf8f20d9f1469cf19f2a725185519c10.pdf (accessed July 29, 2020).

[36] Chicago is an outlier when it comes to the cost of police misconduct, but it is nevertheless instructive to observe that it paid in aggregate $757 million in settlements, losses at trial, and other payouts from 2004-2018. See Dan Hinkel, “A hidden cost of Chicago police misconduct,” Chicago Tribune, September 12, 2019, https://www.chicagotribune.com/investigations/ct-met-chicago-legal-spending-20190912-sky5euto4jbcdenjfi4datpnki-story.html (accessed July 20, 2020).

[37] I want to note that I initially suggested that the committee be called the Committee on Diversity in Comparative-Historical Sociology or something similarly bureaucratic and anodyne. My sense from my research on affirmative action—especially at a moment when Students for Fair Admissions is appealing last year’s decision to uphold Harvard’s affirmative action plan by the U.S. District Court in Massachusetts—led me to think that it might be perfectly fine to lean on the word “diversity” again. But two younger, more thoughtful colleagues on the ASA CHS Council disabused me of the notion, arguing persuasively that it was critically important for a range of reasons to include the terms “Anti-Blackness” and “Racism” in the names of the committee and panel.

*This essay is originally published at Trajectories (Spring/Summer 2020) pp.23-38