(Image: Jones 2017)

Dylan Riley, Rebecca Jean Emigh, and Patricia Ahmed

The 2020 census is likely to be the most politicized national count for decades. The focus of contemporary debate concerns the possible re-instatement of a citizenship question on the general census for the first time since 1950; previously, sample surveys had captured this information (Wines 2018). The Secretary of Commerce’s proposed change is in response to a justice department memorandum of 12 December 2017, which claimed that a citizenship question was necessary in order to “enable the Department [of Justice] to protect all American citizens’ voting rights under Section 2” (Gary 2017). The logic of the DOJ position, as well as an e-mail from the notorious Kansas Secretary of State, Kris Kobach, is that the U.S. census should primarily be about counting citizens for purposes of political apportionment. As Kobach notes in his e-mail, the lack of a citizenship question “leads to the problem that aliens who do not actually ‘reside’ in the United States are still countered for congressional apportionment purposes” (Kobach 2017). This argument has led left liberals, such as Robert Reich (2018) to refer to this plan as “an unconstitutional power grab.” We think it may be useful to place this current controversy in a broader historical context.

We begin by discussing some structural features of the U.S. census. We sketch out some of the features likely to lead to a very highly-politicized census in 2020. We then discuss a period of census debate similar to the current one, focusing on the four censuses from 1890–1920. We conclude by suggesting two key differences between that period and the contemporary one.

Structural Features of Census Taking in the U.S.

The census’s basic purpose is to apportion seats to the House of Representatives and votes to the Electoral College. Importantly, and contra the Trump DOJ and Kobach, representation is not based in the United States on the number of citizens who live in a particular area. It is somewhat paradoxical to find left-liberals pointing this out while self-described “conservatives” seem to have forgotten it. The reason for this peculiarity is that the slave holding states at the Constitutional Convention insisted on partially enumerating slaves in the infamous 3/5ths compromise. But slaves were not citizens, and accordingly, no language in the U.S. Constitution specifies that citizens alone should be counted. The charter stipulates only that an “actual enumeration of the population” should be undertaken.

With the expansion of the U.S. state’s functions since the mid-twentieth century, census information has also been used to distribute federal money. Indeed, as many commentators have pointed out, one of the obvious intended purposes of the administration’s citizenship question is to depress numbers in areas with large numbers of immigrants, thereby depriving them of funds.

These facts suggest why the census is so important, and why it is so potentially politicized. But there is a further peculiarity of the U.S. political system that, like jet fuel on an open flame, massively increases the political temperature of the decennial count.

Political representation in United States Congress is based on gerrymandered single member districts which have been established in a context of massive, although largely asymmetrical, political polarization. To grasp the significance of these features, it may be useful to contrast single member representation with proportional representation. In a single member district, the top vote getter is the only representative from the district, meaning that only the winning party achieves any representation in the district. Multi-member proportional systems, in contrast, distribute seats in proportion to the number of votes each party receives.

In a single member system, winning the majority of the votes in a district has huge political consequences. Districts shift entirely from one party to another often on the basis of a small number of votes. Indeed, in the U.S., political language registers this winner-takes-all system as pundits and the populace speak of “red” or “blue” districts or states: conceptually deleting the often very large groups of “blues” in “red” states and “reds” in “blue” states, as well as the substantial proportion of the population that is alienated from politics altogether.

When this feature is combined with the deep political importance of race and ethnicity in the U.S. context, it implies that determining the distribution of types of people across territories is a profoundly political act. The politicization of the census is thus intrinsic to the purpose of the census and the U.S. system of political representation regardless of any more specific historical conditions.

The Contemporary Politics of the U.S. Census

However, the structure of contemporary U.S. politics is likely to make the 2020 census (and future ones) especially politicized. The main element pushing in this direction is the shrinking demographic base of the Republican Party. The GOP is increasingly a party of elderly, less-educated whites; but the white population is shrinking. Meanwhile, the population as a whole is becoming more educated; but level of education correlates negatively with Republican party identification. These basic demographic trends give the party a powerful incentive to undercount certain parts of the U.S. population. The inclusion of a citizenship question on the census is a central part of this project. The incentives of Democrats are largely speaking the reverse. The Party has a strong political interest in a complete count, and particularly in a count that enumerates historically difficult-to-count populations.

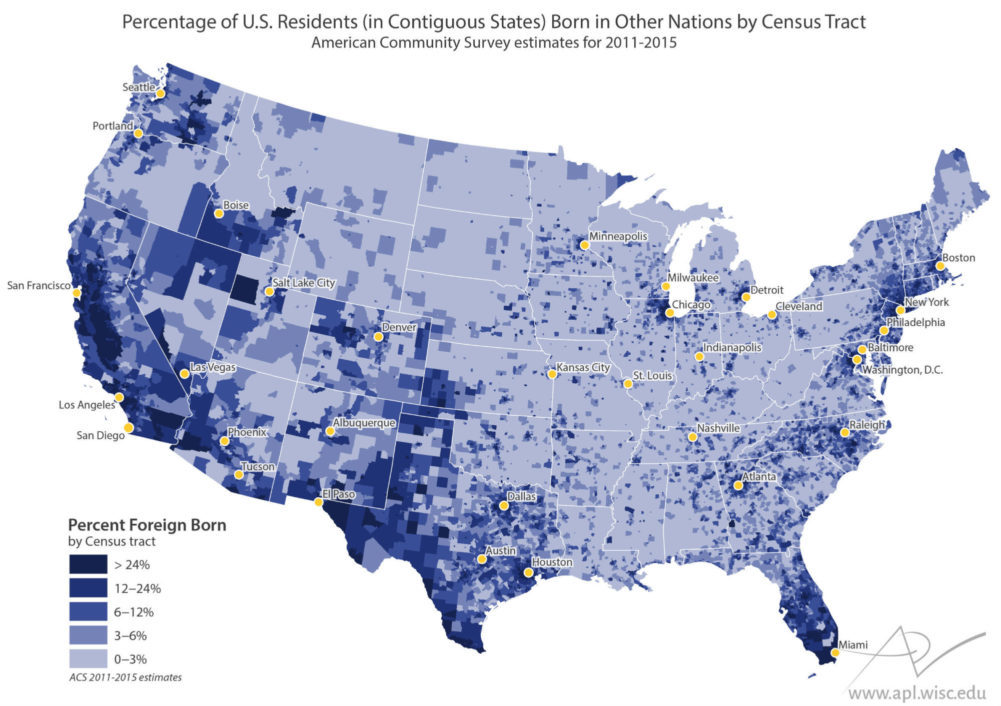

A considerable amount of the demographic change that Republicans fear is driven by migration. There have been three broad phases in the history of mass migration to the United States: a phase stretching from 1850 to 1910, which saw rising percentages of the foreign born population; a second phase of long decline from about 1910 to about 1970 when the foreign population had declined to only 4.7% of the total population; and a last phase stretching from 1970 to today which has seen a steadily rising percentage of the foreign born population until it constituted about 13% of the total U.S. population in 2016 (American Community Survey 2016; Grieco et al. 2012: 19). The U.S.’s recent history of mass immigration is comparable to the period from 1850 to 1910. These immigrant populations have tended to concentrate in coastal “blue areas.” Given the reapportionment mechanisms of the U.S. Constitution, they are a cause of increased political representation for these states.

Thus, the U.S. faces a situation in which one of the two major political parties has an interest in undercounting the population while the other political party has an interest in an extensive count. Combined with the structural features of the U.S. census that lead to its politicization, these facets of the contemporary situation tend to politicize the count even further.

Immigration Worries in the Late Nineteenth Century

There is a clear parallel between this period and that at the turn of the last century when mass immigration created similar incentives for the parties. The years that run from 1890 to 1920 were decisive for much of the subsequent politics of the census in the twentieth century. Mass immigration from southern and eastern Europe, in addition to rising and potentially interracial rural radicalism, posed a profound threat to the WASP establishment that constituted the backbone of the Republican Party. The threat of “new immigrants” from southern and eastern Europe was so severe that in 1920 the Republican-controlled Congress refused to reapportion representation on the basis of the census (Emigh et al. 2016: 62). Under pressure from a powerful eugenics lobby organized as the Immigration Restriction League and connected to Congress through the Immigration Committee, the legislature passed a series of increasingly restrictive immigration laws culminating in the 1924 National Origins Act, which based immigration quotas on the 1890 census (Emigh et al. 2016: 62, 66). Many historians see the National Origins Act as a key moment in the consolidation of “whiteness” among European ethnic groups.

Results and Prospects

We are not the only persons to draw a parallel between contemporary census politics and those of the 1920s. In fact, the current Attorney General of the United States, Jefferson Sessions, has explicitly drawn such a connection. During a radio interview with Breitbart News in 2015, Sessions, stated,

Some people think we have always had these numbers [of immigrants], and it’s not so, it’s very unusual, it’s a radical change. When the numbers reached about this high in 1924, the president and congress changed the policy, and it slowed down immigration significantly, we then assimilated through the 1965 and created really the solid middle class of America, with assimilated immigrants, and it was good for America. We passed a law that went far beyond what anybody realized in 1965, and we’re [now] on a path to surge far past what the situation was in 1924. (Serwer 2017)

Sessions’s comments clearly imply that he sees the 1924 National Origins Act as a model for immigration policy. This well encapsulates the project of the Trump administration. It would like to return the country to a demographic profile reflecting the mid-twentieth century U.S. The census will be a key tool in achieving this.

However, the historical context of census politics in the contemporary period differs from that of the 1920s in two important respects. First, during the earlier period, input about the census was largely constrained to elite-based lobbying. The Immigration Restriction League was funded by prominent private foundations such as the Rockefeller and Kellogg Foundations, and supported by high-powered academics, such as Francis Walker; but since the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, census lobbies with actual mass memberships have played a much more decisive role. We can, therefore, expect any attempt to use the census as a tool in a neo-eugenicist project of whitening the population to face far greater resistance now than similar projects in the 1920s.

The second difference concerns the legitimacy of eugenics as an ideology. In the 1920s, the academic and corporate elite strongly backed the notion of racial improvement, and scientific racism was a respectable intellectual position. Although genetic determinism is a hardy perennial on the border-line between the social sciences and biology (D. Reich 2018), and genetic testing as a way to establish identity seems to have a gained a strange popularity among the broader public, for now it seems unlikely that eugenic thinking will sweep elite opinion in a way analogous to the 1920s.

Conclusion

Controversy over the census is nothing new. Politicization is built into the central role that the census plays in determining political representation. Features of the contemporary political landscape, where the parties have sharply opposed interests in securing an accurate count, exacerbate the phenomenon. Indeed, the contemporary period of census politics closely resembles that of the period from 1890 to 1920, when the census was used to implement exclusionist immigration policies, in important ways; members of the Trump administration are aware of the parallel, and are deliberately seeking to recreate these policies. However, the transition from the politics of elite lobbying that marked the censuses of the earlier period, to the politics of mass lobbying and social movements that mark the censuses since 1965, combined with the fundamental loss of legitimacy of eugenic thinking, will constitute obstacles to any Trumpist attempt to re-play the census politics of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Dylan Riley is Professor of Sociology at University of California, Berkeley. His work uses comparative and historical methods to challenge a set of key conceptual oppositions in classical sociological theory: authoritarianism and democracy, revolution and counter-revolution, and state and society.

Rebecca Jean Emigh is Professor of Sociology at University of California, Los Angeles. Her research focuses on how cultural, economic, and demographic factors intersect to create long-term processes of social change.

Patricia Ahmed is Professor of Sociology at South Dakota State University. She specializes in structural adjustments and censuses.

References

American Community Survey. 2016. “Place of Birth for Foreign Born Population.” Accessible at: https://www.socialexplorer.com/tables/ACS2016_5yr/R11736787

Emigh, Rebecca Jean, Dylan Riley, and Patricia Ahmed. 2016. Changes in Censuses from Imperialist to Welfare States. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gary, Arthur E. 2017. Letter of 12 December 2017. Accessible at: https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/4500011/1-18-Cv-02921-Administrative-Record.pdf

Grieco, Elizabeth M., Edward Trevelyan, Luke Larsen, Yesenia D. Acosta, Christine Gambino, Patricia de la Cruz, Tom Gryn, and Nathan Walters. 2012. “The Size, Place of Birth, and Geographic Distribution of the Foreign-Born Population in the United States: 1960 to 2010.” Working paper. Accessible at: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2012/demo/POP-twps0096.pdf

Kobach, Kris. 2017. Electronic Mail Message of 14 July 2017. Accessible at: https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/4500011/1-18-Cv-02921-Administrative-Record.pdf

Jones, Malia. 2017. “The Changing Faces Of Wisconsin’s Foreign-Born Residents.” WisCONTEXT, 31 May. Available at: https://www.wiscontext.org/changing-faces-wisconsins-foreign-born-residents Graphics by Caitlin McKown and Casey Kalman.

Reich, David. 2018. “How Genetics is Changing Our Understanding of ‘Race’.” The New York Times, online edition, 23 March. Accessible at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/23/opinion/sunday/genetics-race.html

Reich, Robert. 2018. “The Unconstitutional Census Power Grab.” Robertreich.org, 6 June. Accessible at: http://robertreich.org

Serwer, Adam. 2017. Jeff Session’s Unqualified Praise for a 1924 Immigration Law. The Atlantic, online edition, 10 January. Accessible at: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/01/jeff-sessions-1924-immigration/512591/

Wines, Michael. 2018. “Lawsuit Says Citizenship Question on Census Targets Minorities for Political Gain.” New York Times, online edition, 31 May. Accessible at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/31/us/politics/2020-census-citizenship.html